The 21st Century Cures Act, enacted in 2016, aims to accelerate the development of medical products and treatments while promoting patient access to protected health information (PHI). This meant officially prohibiting information blocking, but there re some exceptions.

To achieve these goals, the Cures Act introduced new rules and regulations to prevent information blocking. To ensure compliance, healthcare providers, front office workers, and medical records staff must understand these new rules.

The Cures Act carries devastating penalties, and organizations that engage in information blocking may end up on a public “Wall of Shame” website, tarnishing their hard-earned reputation.

This does not mean you must release all requested medical records, however. There are types of PHI disclosures that are still not acceptable and situations where denial is appropriate.

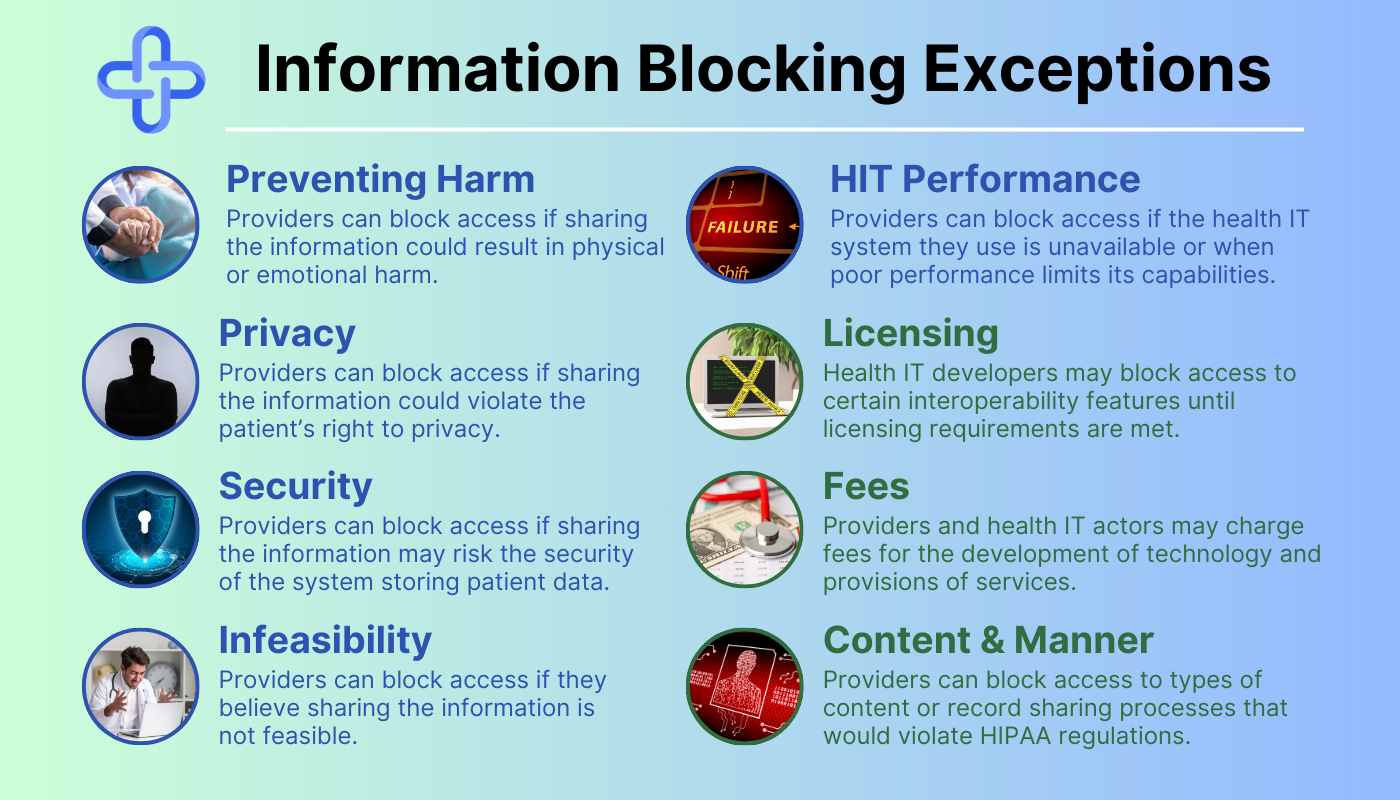

For these situations, there are 8 information-blocking exceptions that you must understand.

Overview of the Cures Act

The 21st Century Cures Act defines information blocking as a practice that “is likely to interfere with, prevent, or materially discourage access, exchange, or use of electronic health information (EHI).” It’s important to note that EHI includes all electronically protected health information (ePHI) created, maintained, or transmitted by a covered entity or business associate.

The act also establishes penalties for information blocking, including civil monetary fines of up to $1 million per violation. Additionally, providers who engage in information blocking may be subject to reduced payments from government programs like Medicare and Medicaid.

The Difference Between the Two Categories of Information Blocking Exceptions

There are two categories of information-blocking exceptions.

- The first category includes exceptions that involve not fulfilling requests to access, exchange, or use PHI.

- The second category involves procedures for fulfilling requests to access, exchange, or use EHI.

Pedantic or confusing? Don’t worry; making the distinction between the information-blocking exception categories is easier than it seems.

Information Blocking Exceptions: Category 1

Information blocking exceptions in the first category cover situations where providers decline to disclose PHI in the requested manner. This category extends to requests that need to be released in a different format, time, or not released at all.

There are 5 information-blocking exceptions in this category:

- Preventing Harm

- Privacy

- Security

- Infeasibility

- Health IT Performance

The Preventing Harm Exception

Bad news related to a patient’s health can cause immense mental and emotional strain. The response patients have to this type of news can directly impact them and the people around them.

The goal of medical professionals is to improve the health of the general population. The Preventing Harm Exception enables doctors to use their judgment to determine whether it’s safe to release sensitive medical information.

With this information blocking exception, providers can block access to requested medical records if they believe that sharing the information could result in physical or emotional harm to the patient or another individual. The exception applies even if the patient requests the information using a valid, signed HIPAA authorization form.

Real-Life Example of the Preventing Harm Exception

Imagine a patient with a known history of stress-induced violent outbursts who requests access to a recent HIV test. If this test indicated the patient was HIV-positive, the doctor may decide that sharing the results could cause the patient to harm themself or another individual.

The Privacy Exception

Enhancing patient privacy is one of the core tenets of HIPAA. There’s no shortage of bad actors targeting healthcare organizations to steal personal information, and disclosure of sensitive information can dramatically impact patients’ lives.

The Cures Act does not aim to replace HIPAA, despite the alignment of key goals. If you’re ever confused about seemingly contradictory messaging between the Cures Act and HIPAA, remember to prioritize HIPAA.

This information-blocking exception allows providers to block access if they believe sharing the information could violate the patient’s right to privacy. Providers can use this exception if they have a reasonable belief that sharing the EHI would disclose sensitive information, such as information related to mental health, substance abuse, or other personal matters.

Real-Life Example of the Privacy Exception

Imagine receiving a request from a researcher for medical records that the patient specifically requested their provider to withhold. In this situation, the healthcare provider can use this exception to protect the privacy of their patient.

The Security Exception

Security is another core tenet of HIPAA, and this exception enables providers to protect their databases without fear of penalties. This exception generally only delays the fulfillment of EHI requests, rather than outright denial.

Providers using the security exception aim to prevent cyberattacks and data breaches. They may block access to EHI if they believe that sharing the information could compromise the security of the health IT system storing patient data.

This exception also applies to situations where a provider has a reasonable belief that sharing the EHI could expose vulnerabilities in their health IT system, such as security flaws or other weaknesses.

Real-Life Example of the Security Exception

Imagine a patient who requests records while a provider’s system is on lockdown while health IT professionals remove malware. While the issue persists, connecting the system to the internet and accessing records could cause a breach. In this situation, the provider may block access to the patient’s information until they can secure their system.

The Infeasibility Exception

While the Cures Act set requirements for Health IT interoperability, not all healthcare organizations have caught up. A goal of the Cures Act is to empower requestors to get medical records in their preferred format, but this isn’t always possible.

The infeasibility exception allows providers to block access to EHI if they believe that sharing the information is not feasible. This could be due to technical capabilities, logistical issues, or legal rights. For example, if the EHI is stored in a format that is not compatible with the recipient’s health IT system.

Real-Life Example of the Infeasibility Exception

Imagine a patient submitting a request for ePHI from a provider whose system is down due to a natural disaster. In this case, it’s not possible for the provider to release the records due to circumstances beyond their control. In most cases, the infeasibility exception either delays request fulfillment or adjusts how the request is fulfilled.

The Health IT Performance Exception

Like most commercial software, health IT platforms are constantly undergoing further development to avoid becoming obsolete. Failure to improve existing software can cause security weaknesses, poor performance, and other issues.

The Health IT Performance exception recognizes that maintenance and improvements to software can require it to be taken offline temporarily. This information-blocking exception protects providers when reasonable and necessary measures make health IT unavailable, or when poor performance limits its capabilities.

Real-Life Example of the Health IT Performance Exception

Imagine a patient requesting records from a provider, only to find their EHR system is experiencing major performance issues. This information-blocking exception enables the provider to limit access to non-essential information until the issue is resolved.

Information Blocking Exceptions: Category 2

The second category is for requests that cannot be fulfilled without taking additional steps. These exceptions generally delay the release of information due to monetary or compatibility issues with the requested method of release.

There are 3 information-blocking exceptions in this category:

- Licensing

- Fees

- Content and Manner

The Licensing Exception

If you’ve ever used the free version of Microsoft Office or tried to access Adobe programs, you may have seen a message about entering a license code. This is essentially a password you receive upon payment for the software, and it helps companies prevent software piracy.

This exception allows developers to protect the value of their innovations from piracy and charge reasonable royalties. Health IT organizations are generally for-profit companies, and this also helps them earn returns on the investments they have made to develop, maintain, and update those innovations.

Generally speaking, this exception won’t be used for the provision of care. Rather, it’s designed for large requests for data, such as those between health IT applications.

Real-Life Example of the Licensing Exception

Imagine a healthcare provider who wants to enhance their EHR system using a secondary health IT platform. This exception allows the second platform to withhold certain interoperability elements until the provider meets the terms of licensing.

The Fees Exception

Health IT organizations must follow strict security and compliance regulations while developing new solutions, and this generally requires a team of various types of specialists. Compliance officers, lawyers, teams of developers, and a myriad of other professionals are behind each platform you use.

Similarly, your organization likely puts significant effort into releasing requested medical records as quickly as possible.

This exception enables both healthcare and health IT actors to charge fees related to the development of technologies and provisions of services that enhance interoperability. This does not enable rent-seeking, opportunistic fees, or exclusionary practices that interfere with access, exchange, or use of EHI.

Real-Life Example of the Fees Exception

Imagine a patient is requesting medical records from a healthcare provider, and the provider has a compliant pricing program implemented. This exception allows the provider to collect reasonable, cost-based payment for the release of information.

Release of information software can help you collect payment for the release of information, so you can stop missing out on revenue.

The Content and Manner Exception

As mentioned earlier, HIPAA takes priority over the Cures Act. HIPAA also outlines how providers can disclose PHI and what types of records they can disclose.

The content and manner exception allows providers to decline requests for content that would violate HIPAA, such as psychotherapy notes.

This information-blocking exception also allows providers to decline disclosures requested in a manner that would violate HIPAA.

Real-Life Example of the Content and Manner Exception

Imagine a patient submitting a request for medical records to a healthcare provider. In this request, they ask the provider to text screenshots of their records because it’s the most convenient option.

Texting is generally not a compliant method of disclosure, so the provider is able to decline the manner of release and suggest alternative options.

Best Practices for Using the Information Blocking Exceptions

While the information-blocking exceptions exist for healthcare providers to use when necessary, patients may not understand why their requests are denied. It’s easy for requestors to submit information-blocking claims, so you must help keep them informed.

Here is a list of best practices your team should follow when using the information-blocking exceptions to decline or adjust requests:

- Develop clear and concise policies and procedures for responding to requests for PHI. These policies should outline the steps that staff members should take when receiving requests, including request evaluation and how to handle applicable exceptions.

- Train staff members on the Cures Act and the importance of following your organization’s compliance plan. This training should be ongoing and should include updates as new guidance is released. It should also cover the information blocking exceptions and how to evaluate requests for information.

- Ensure that all EHR systems are compatible with other providers’ systems to facilitate the exchange of EHI. This may involve upgrading existing systems or implementing new systems that meet interoperability standards.

- Monitor compliance with the Cures Act and take corrective action if necessary. This may involve conducting periodic audits of policies and procedures or evaluating staff members’ compliance with training requirements.

- Document all requests for access, exchange, or use of PHI, as well as any exceptions that apply. This documentation should include the reason for the exception and the steps taken to address it.

- Develop a process for responding to patient complaints or concerns about access to their health information. This may involve designating a point person to handle complaints or establishing a dedicated hotline or email address for patients to use.

- Use technology and health IT systems that facilitate the secure exchange of patient information while also allowing for the appropriate use of information-blocking exceptions.