After a year defined by a worldwide pandemic, a new generation witnessed the havoc a contagion can wreak. Unfortunately, the future of public health may hold more grim chapters.

Drug-resistant bacteria are a universal concern, as over 700,000 people die each year from previously curable infections and diseases. If antibiotic-resistant infections go unchecked, issues as minor as ear infections, urinary tract infections, or sore throats could prove dire. Strep throat, for example, could be life-threatening if antibiotics do not work.

Based on the 2019 report by the UN Ad hoc Interagency Coordination Group on Antimicrobial Resistance, we must develop additional defenses. The report explains that “by 2050…,” drug-resistant pathogens could cause 10 million deaths each year. At the time of writing, that’s more than double the reported deaths caused by Covid-19.

As bacteria continue to evolve immunity to our antibiotics, it is urgent that we find answers. One potential savior can be found by looking to the past — or through an electron microscope.

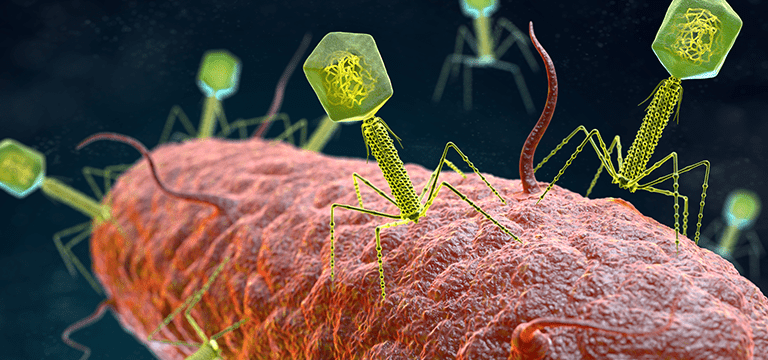

THE BACTERIOPHAGE

A bacteriophage is a type of virus that kills a specific bacteria. Its discovery is attributed to both British investigator Frederick Twort in 1915 and French-Canadian scientist Félix d’Hérelle in 1917. D’Hérelle proceeded to pursue a thorough study to prove his findings.

Its head, or capsid, contains the phage’s genetic material. Attached by the collar is the tail. This consists of a long tube called a sheath, six legs called tail fibers, and spikes attached by a base plate.

Whereas using antibiotics is comparable to carpet bombing the bacteria in your body, the bacteriophage is more like a guided missile. It explores its environment in search of its only prey, ignoring all other bacteria.

Once it finds its target, the bacteriophage used in healthcare settings will begin the lytic cycle. The phage lands on the bacteria’s outer membrane pierces it and injects its DNA to rewrite the bacteria’s DNA.

The bacteria then invests all its energy and resources to create copies of the phage. Late in the process, the phage pokes holes into the walls of the membrane. As water rushes into the cell, the pressure grows too great. The bacteria burst, releasing hundreds of phages to begin the process anew.

Phage therapy has seen continued use in some countries, especially Georgia, Russia, and Poland. There are several reasons western medical professionals did not embrace bacteriophage treatment, however. The three main :

- Historic

- Medical

- Regulatory

History of the bacteriophage

The Eliava Institute in Tbilisi, Georgia was the first of its kind. Georgian bacteriologist and phage researcher Prof. George Eliava founded the facility in 1923 and developed it with help from d’Hérelle. The facility still operates today, despite Eliava’s execution in 1937 under Stalin’s reign of terror.

Bacteriophage played a major part in Russian military efforts during the Winter War with Finland (1939-1940) and World War 2 (1939-1945). After surviving the siege of Leningrad (1941-1944), Soviet science fiction author Boris Strugatsky shared his recollection:

Then, in March, I came down with the so-called bloody diarrhea, an infectious disease that is dangerous even for a grown, portly man, and I was eight years old, and had dystrophy – a certain death, one would think. But our neighbor (who also miraculously survived) somehow happened to have a vial of bacteriophage, so I lived.

“Lichnost′: Boris Strugatskii,” Argumenty i Fakty, 21 May 2001.

Soldiers also carried vials of bacteriophage to kill the bacteria that caused dysentery and infected wounds. Despite saving untold lives throughout dark times, phage research decreased during the Cold War outside Georgia.

Medical competition and limitations

Discovered in 1928 by the Scottish physician and scientist Alexander Fleming, penicillin was one of the most groundbreaking revolutions in human history. Neither phage nor antibiotics help treat viral infections like the common cold.

Treating with antibiotics is a simple and effective method of eliminating bacterial infections. Unlike the phage, penicillin treats bacterial infections and diseases without the physician needing to know the invisible microbe’s identity.

Antibiotic treatment isn’t without cons, though. 10% of U.S. patients report allergic reactions to penicillin. Additionally, the common side effects caused by antibiotics’ assault on the body’s beneficial bacteria cause several potential digestive issues.

Despite this, the effectiveness and ease of penicillin treatment made phage therapy fall into obscurity. Bacteriophage therapy has some additional cons too, such as the specificity required to utilize a phage.

Screening for a positive match to a bacteria is incredibly tedious. Scientists who study the phage hunt for new specimens in sewers, lakes, and other areas of bacteria-infested water. They take process, and log these samples in search of treatments for prioritized diseases.

This makes treatment with phage specialized, as an identical batch of phage cocktails must be created each time more is needed. Additionally, a physician must diagnose the full array of bacteria before a phage can be effectively utilized.

Also, as it does with antibiotics, bacteria can evolve to be resistant to phage treatment. This is surprisingly not a downside to phage therapy though, as the bacteria’s DNA has limited space. The bacteria is forced to give up some of its drug resistance to gain new phage resistance. A course of antibiotics and phage can theoretically work in tandem to fight the nastiest antibiotic-resistant bacteria out there.

Regulatory burden

The FDA has not approved Bacteriophage for human treatment because each specimen is so specialized. Each time a phage is used in this manner, it must undergo emergency approval for the individual. Additionally, because antibiotics are generally safe and effective, there hasn’t been a push to fund major research.

The FDA can approve phage cocktails for a patient if they have no other feasible hope of survival. The most well-known case follows Tom Patterson, Ph.D., a professor at UC San Diego School of Medicine. He fell into a coma due to a multidrug-resistant strain of Acinetobacter baumanii in his chest.

In 2016, he became the first patient in the United States to successfully undergo intravenous phage therapy. Within two days of the first treatment, he had awoken from the coma.

Since then, there have been dozens of further bacteriophage treatments in the United States, and many show promising results. Additionally, there are multiple clinical trials with dedicated scientists testing phage’s ability to combat microbial-resistant bacteria.

How ChartRequest Can Assist in Clinical Trials

Ensuring patient safety in a clinical trial is essential. Reviewing the patient’s medical records is a key step in screening the applicants. Gaining access to the records can be a complicated, burdensome process, but ChartRequest can help. You can receive